Covid-19: Critical or Wicked for Boris?

Apr 28, 2020

Some problems are so complex that you have to be highly intelligent and well informed just to be undecided about them. [Peter's Almanac, 1982]

At the beginning of 2019, the job of British Prime Minister seemed like a poisoned chalice. But by that stage Brexit could be construed by any spin-doctor worth his salt as a crisis, and a crisis was just what Boris Johnson needed.

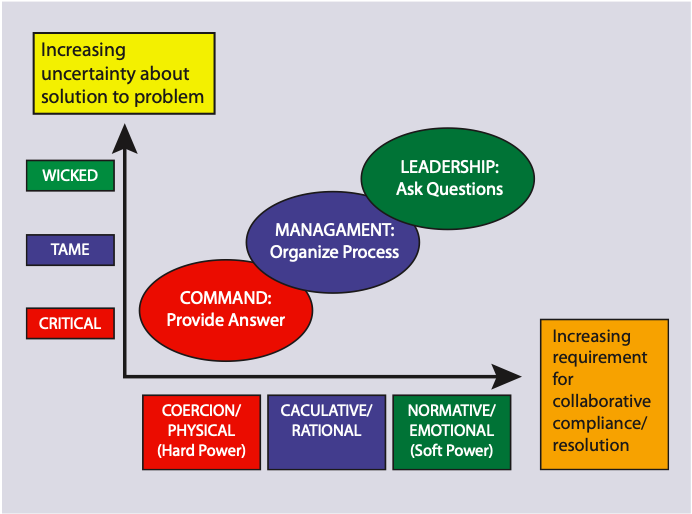

In Wicked Problems and Clumsy Solutions: the Role of Leadership (2008), Keith Grint summarises the concept of Critical, Tame and Wicked problems in relation to certainty and collaboration.

Everyone accepts that a critical problem (like a house on fire) requires a Command-style response. Boris stepped into the role of Commander-in-Chief with ease, brushing off every demand for consultation and collaboration in an extraordinary display of focus and defiance. The problem is clear, and so is the answer: Get Brexit Done. The British public - it turned out - liked that.

One year later, Britain is assaulted by a new challenge, and so is Boris. Covid-19 seems like another critical problem, but unlike the house on fire, there is much less certainty about the solution, as Boris team wisely admits. Now we must follow the science, which might be construing the problem as tame. A tame problem is not necessarily easy, but does follow tried and tested pathways, relying on accurate analysis and well-developed procedures to solve it. Its a refreshing change of tone, rational rather than political, collaborative rather than dictatorial.

But the uncertainty factor is higher than that, and we all know it. This is a wicked problem, one that no one has met before, so we really dont know what the process is or what the rules should be. A wicked problem demands not just good management, but creative leadership which focuses on asking the right questions and connecting the right people, because it will only be solved when maximum resources are mobilised.

Leadership, says Grint, is more of an art than a science, the art of engaging a community in facing up to complex problems.

Many decision-makers will try to avoid such leadership at all costs, because it suggests

- the leader does not know the answer

- the leader must help followers face up to their responsibilities

- the answer will take time

- it will be appropriate rather than the best

- it will take constant effort to maintain.

An easier route might be to fall back into smoke and mirror certainties, the policing of truth and quasi-heroic solutions. I doubt if Boris will ever receive a round of applause from millions of British residents as the NHS workers did. Yet the kind of leaders who help solve wicked problems are those who succeed in unleashing and acknowledging creativity and sacrifice in others. Do we dare hope and pray that in the wake of his deeply personal encounter with Covid-19, Boris might yet choose wise leadership over political expediency?